Our brains are increasingly plastic, a new study finds.

Researchers have just pored over samples of brain tissue collected over 25 years. Surprisingly high levels of tiny plastic shards litter our noggins, they find. And recent samples had more microplastics, on average, than did older ones.

Super-small plastic bits have shown up in earlier studies. They’ve been littering our lungs, intestines, blood and liver. But levels found in the brain are higher than those seen elsewhere in the body.

The new brain measurements were reported February 3 in Nature Medicine.

Raffaele Marfella is a heart researcher at University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli” in Naples, Italy. He did not take part in the new study but has studied microplastic risks in people. The new findings are “both significant and concerning,” he says. After all, earlier studies have linked elevated blood levels of plastic bits with an increased risk of heart attacks, strokes and death.

A second study, due to be reported soon, finds hints that plastic pollution might also affect neural — brain — function. People living in coastal areas where seawater had especially high levels of tiny plastic bits were more likely to report a range of problems. These ranged from difficulty performing cognitive tasks (like thinking and memory) to problems getting around and taking care of normal daily tasks.

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores

Levels found ‘are almost unbelievable’

For the brain study, researchers pored over 91 tissue samples. Each came from someone who had died and donated their organs to science.

Measuring micro- and nano- sized plastic bits in them — MNPs, for short — proved tricky. So the researchers used several techniques.

How much plastic turned up seems to be climbing quickly. The average mass of plastic in brain tissue was 3,345 micrograms per gram in 2016. Eight years later, it was 4,917 micrograms per gram. That’s an increase of some 50 percent.

“Levels of plastic being detected in the brain are almost unbelievable,” says study coauthor Andrew West. “In fact, I didn’t believe it until I saw all the data” from multiple tests with different samples, he says. A neuroscientist, West works at Duke University in Durham, N.C.

Levels may be unbelievable to West, but they didn’t surprise Richard Thompson. He’s a microplastics expert at the University of Plymouth in England. He even coauthored one of the first reports on microplastics pollution in the environment back in 2011.

These itty bits “are in the food we eat, the water we drink and even the air we breathe,” Thompson points out. So he wasn’t surprised they’re finding their way into us.

Brainy surprise

The brain has a cellular do-not-pass zone. It’s called the blood-brain barrier. It keeps many of the wrong things from entering the brain. Scientists had wondered if it would keep out plastic, too. But the new data show that microplastics have breached that barrier.

In fact, brain samples from 2024 hosted some 10 times more plastic than did liver and kidney samples. But not everyone had high levels. West says his group is now curious how some people actually seemed to have avoided a buildup.

“This study clearly demonstrates that they are there — and in high concentrations,” says Phoebe Stapleton. She’s a toxicologist at Rutgers University. That’s in Piscataway, N.J.

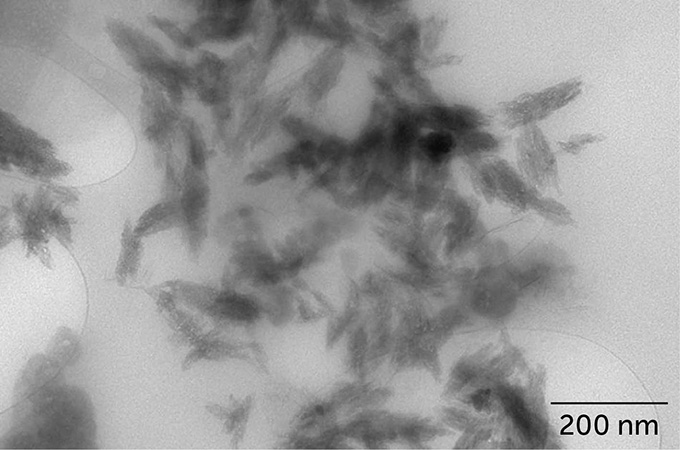

Stapleton says the shape of those bits is are a surprise.

Plastic bits in lab studies tend to look like beads. “The aged shards that wind up in the brain,” West now reports, “look like nothing we have used yet in the lab.” They’re long, sharp particles.

Many of those lab studies had tested micro- and nano-sized beads of polystyrene. The brain had little of this plastic. There was, however, lots of polyethylene. It’s a common plastic used in such things as grocery bags, shampoo bottles and toys.

Should we be worried?

What do these findings mean? West’s team isn’t sure. For instance, it found no link between MNP levels and age at death. But the number of samples they tested was fairly small. Interpreting the measurements also was hard. And there’s always the risk that some tiny plastic bits in the air might have contaminated the samples.

This study also didn’t track plastic levels over time in living people. So the research can’t say how someone’s pollution levels may change with time.

Perhaps the biggest unanswered question: Are they harmful? “Simply put,” West says, “we do not know the health implications of microplastics in the brain.” But, he adds, it would be a mistake to wait to get all the answers before addressing the issue.

A second new study bolsters concern about plastic pollution, says Sarju Ganatra. He’s a cardiologist and sustainability researcher at Lahey Hospital & Medical Center in Burlington, Mass. “Our health is tightly integrated with the planetary health,” he says — including “the air we breathe, the water we drink and the food we eat.” Plastic bits are contaminating all of these. So his team wondered what they might be doing to people.

To make a quick gauge of this, they tracked down a national database of self-reported nerve-related (including brain-related) disabilities. They focused on data for people living in 218 U.S. coastal counties. The people surveyed were chosen to be representative of everyone living throughout these counties — more than 6 million people.

Ganatra’s group then cross-referenced disability rates in these people against average levels of MNPs in local seawater. Those values had been collected by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Plastic quantities ranged from 10 or fewer MNPs per cubic meter of seawater to 7,000 or more.

Where MNP levels in water had been highest, people showed a rate of disability in cognition (thinking and memory) 9 percent higher than in those living where coastal waters had the lowest MNP levels. Those in the highest group also were more likely to have problems taking care of themselves (such as dressing, shopping and getting around their community).

Ganatra’s team shared its findings the week of April 5. They presented at the American Academy of Neurology meeting in San Diego, Calif.

These data don’t prove that MNPs caused the reported disabilities, Ganatra says. They’ve only found an association. But spotting such associations, he says, is “what drives the science.” They point to where scientists should probe deeper through follow-up tests.

Indeed, Ganatra told Science News Explores, “We need to start thinking about how do we start to measure these microplastics in individual patients.” That’s a first step, he says, in seeing how they might be linked to diseases affecting such things as the brain, hormone systems and the heart.

Says Ganatra: “Being the father of an eight-year-old, I think it’s important that we start thinking in this direction.”