Sex isn’t as simple as male or female.

It’s not just about chromosomes. Or genitals. Or reproductive cells. Or any other binary metric. (Binary refers to something that can only take one of two, either/or states.)

People have a huge range of genetic, environmental and developmental variations. These can produce in the same person a mix of what are thought of as masculine and feminine traits. When it comes to sex, millions of people don’t fit a narrow, binary definition. That’s through no fault of their own — and many don’t even know it. Instead, scientists say, sex should be viewed in all its complex glory.

“Sex is a multifaceted trait that has some components that are present at birth and some components that developed during puberty,” says Sam Sharpe. “And each of these components shows variation.” Sharpe is an evolutionary biologist at Kansas State University in Manhattan.

This underscores the challenge with trying to say someone is male or female based on just one trait, such as what reproductive cells (eggs or sperm) they can make.

In fact, defining sex by just the size of sex cells “reduces a human being to their chance of reproducing,” notes Anna Biason-Lauber. She calls this type of definition “really painful.” A pediatric endocrinologist, she works at the University of Fribourg in Switzerland.

What’s more, such a definition is not biologically accurate. It leaves out people who don’t make any reproductive cells, also called gametes. That can be caused by being born with certain genetic variants.

“What does that mean for people who don’t have gametes?” Sharpe asks. “That is, as of now, an unanswered question. But it’s an important question to answer, because you can’t have a definition of sex that doesn’t apply to everyone.”

A person’s defined sex may affect many aspects of daily life, such as which public restroom they can use. Or getting an ID card or passport. Or joining a sports team. So any definition of sex needs to account for existing variation, Sharpe and other researchers say.

Sex is complicated

“Biology doesn’t operate in binaries very often,” says Nathan Lents. He’s a molecular evolutionary biologist at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City.

Reproductive cells are about as close to a true binary as nature gets, he says. There are two types of gametes, eggs and sperm. Egg cells are much larger than sperm.

But sex is much more than types of reproductive cells, he and other researchers point out.

Most traits ascribed to males and females fall along a spectrum that has two peaks. One is the average for females. The other is the average for males. On average, males are taller than females. Males also, on average, have more muscle mass, more red blood cells and a higher metabolism.

But almost nobody fits in the peak for their sex on all of those measures, Lents says. “There’s plenty of women who are taller than plenty of men,” he says, or “who have higher metabolic rates than some men.”

A definition of biological sex based just on gametes misses all that complexity. “You’re going to ignore most of what actually matters to your daily life,” he says.

When does sex develop?

Human sex development starts in the womb. The exact timing is hard to pinpoint, but it’s several weeks after conception, Biason-Lauber says.

Scientists used to think that embryos automatically developed as female unless there were specific instructions to become male. But in the last decade, researchers have learned that’s not true. To develop as females, embryos must actively dismantle male-producing structures. And they have to build ones that support female reproduction.

About six weeks into gestation, cells appear that will eventually give rise to ovaries (the tissue that makes eggs) or testes (the tissue that can make sperm). But for a couple of weeks, Biason-Lauber says, those cells are “absolutely indistinguishable” from each other.

At about eight weeks into gestation, certain cells in what will become the testes begin to make testosterone. This hormone is important for development of the scrotum and penis and other male reproductive organs. But males don’t make sperm at this point. That’s because testosterone levels dip late in pregnancy. And they stay low until puberty. Then testosterone kicks in once more. At this point, immature cells can morph into sperm.

Ovaries don’t produce any sex hormones in the fetus. And the uterus, fallopian tubes and vagina develop without any input from hormones, Biason-Lauber says. Females are born with all the eggs they will ever make. Those cells are in a state of suspended animation, though. They’ll stay that way until puberty. Only then can they mature and start being released.

Sex chromosomes can have lots of variation

Those developmental processes are partially directed by X and Y chromosomes. Though often called sex chromosomes, that name is somewhat misleading. In fact, the X and Y chromosomes have a wide range of jobs.

The X chromosome contains hundreds of genes. They play a role in processes throughout the body. Blood clotting, color vision and brain development are just a few. The Y chromosome is much smaller with many fewer genes. It does contain genes important for male sex development and fertility. But other genes on it play a role in immunity, heart health and cancer.

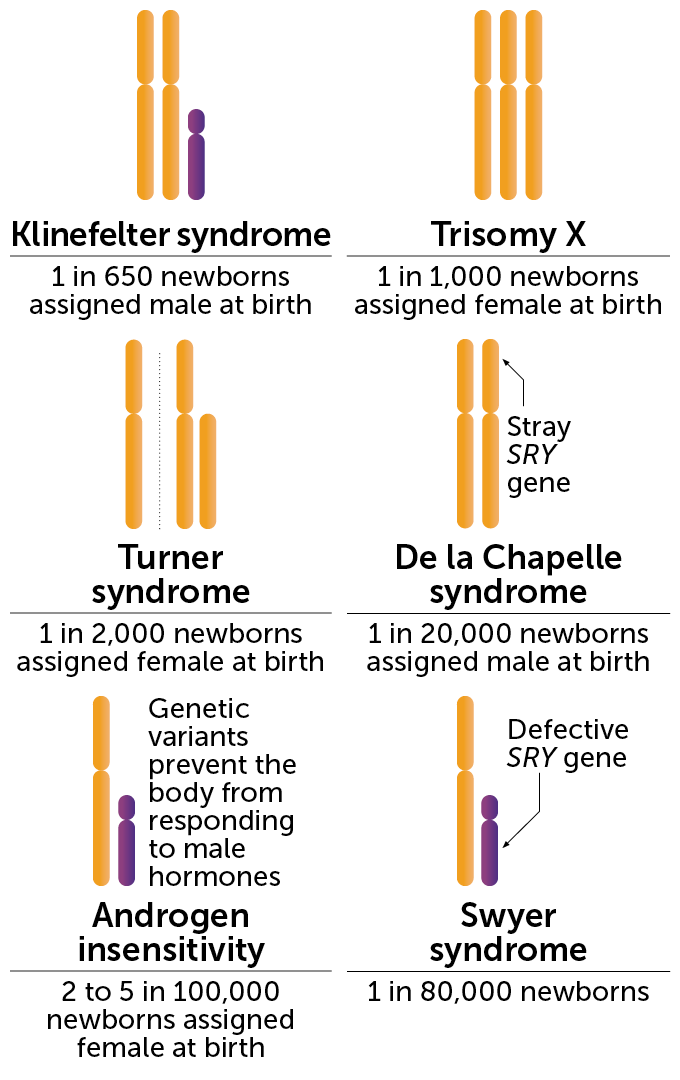

Females generally have two X chromosomes. Males typically have an X and a Y. But there are plenty of variations on that theme, Biason-Lauber notes.

For instance, in Turner syndrome, women lack one X chromosome. They do have a uterus, but no ovaries. So they can’t make gametes. If sex were defined by which gamete you make, Biason-Lauber wonders, what sex would someone with Turner syndrome be? And this condition is not all that rare, she adds. Some 1 of every 2,000 to 2,500 female babies are born with it. Many won’t find out until adulthood. Others may never be diagnosed.

About 1 in every 650 male babies are born with two or more X chromosomes and one Y. This is called Klinefelter syndrome. Many men with this won’t learn they have an extra chromosome unless they go for fertility treatments, Biason-Lauber says. These people have testes and penises. They don’t, however, make sperm. So a definition based on gametes would leave these people out.

One gene on the Y chromosome is called SRY. It is important, but not essential, for male sex development. Sometimes, SRY jumps out of the Y chromosome when chromosomes are divvied up before sperm production. It can attach itself to an X or some other chromosome. If the hitchhiking SRY gene is passed on, it may result in people who have two X chromosomes plus a stray SRY gene. These people will develop as males. But lacking a full Y chromosome, they won’t make sperm.

Some people have an X and a Y chromosome but carry a version of SRY — or changes in other genes — that doesn’t spur typical male development. These people develop as females but don’t make eggs.

Other people with an X and a Y may have versions of some genes that prevent their bodies from responding to testosterone and other male sex hormones. Those people have testes inside their abdomens. But the rest of their bodies develop as female.

Variants in many other genes may also prevent production of either eggs or sperm. Some people even have different combinations of sex chromosomes in different cells of their bodies.

Being intersex isn’t all that rare

In practice, a person’s sex is usually assigned at birth based on external genitals. A baby with a vulva is labeled a girl. A baby with testes and a penis is labeled a boy.

But even at birth, some people don’t fit neatly into male or female boxes. About 1.7 percent of the population is intersex. That’s according to InterAct, an advocacy organization for intersex youth. This rate is as common as having naturally red hair.

Sex development in intersex people can differ in any of a wide variety of ways, including those described above. Some may be born with both ovarian and testicular tissue. Under some definitions of sex, they might be considered both male and female, says Sylvan Fraser Anthony, InterAct’s legal and policy director.

Intersex individuals often undergo surgeries as infants or young children to make their genitals or internal organs conform to the sex their parents choose. They may also need to take hormones (such as estrogen or testosterone) to maintain their health, says Sharpe.

Such sex hormones also “play an important role in many facets of development,” Sharpe says. This includes “whether your skin is painfully dry or not. Or how tall you grow during puberty. Or whether you’re able to maintain bone density.”

With so much natural variation among people, trying to define sex by any single factor is bound to create confusion. Plus, unless they need to for medical reasons, most people never have their gametes or chromosomes checked. So neither is a practical way to define whether someone is male or female.

“The biology of sex and gender makes it very clear,” Lents says. “These are not hard categories with clear definitions.”

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores