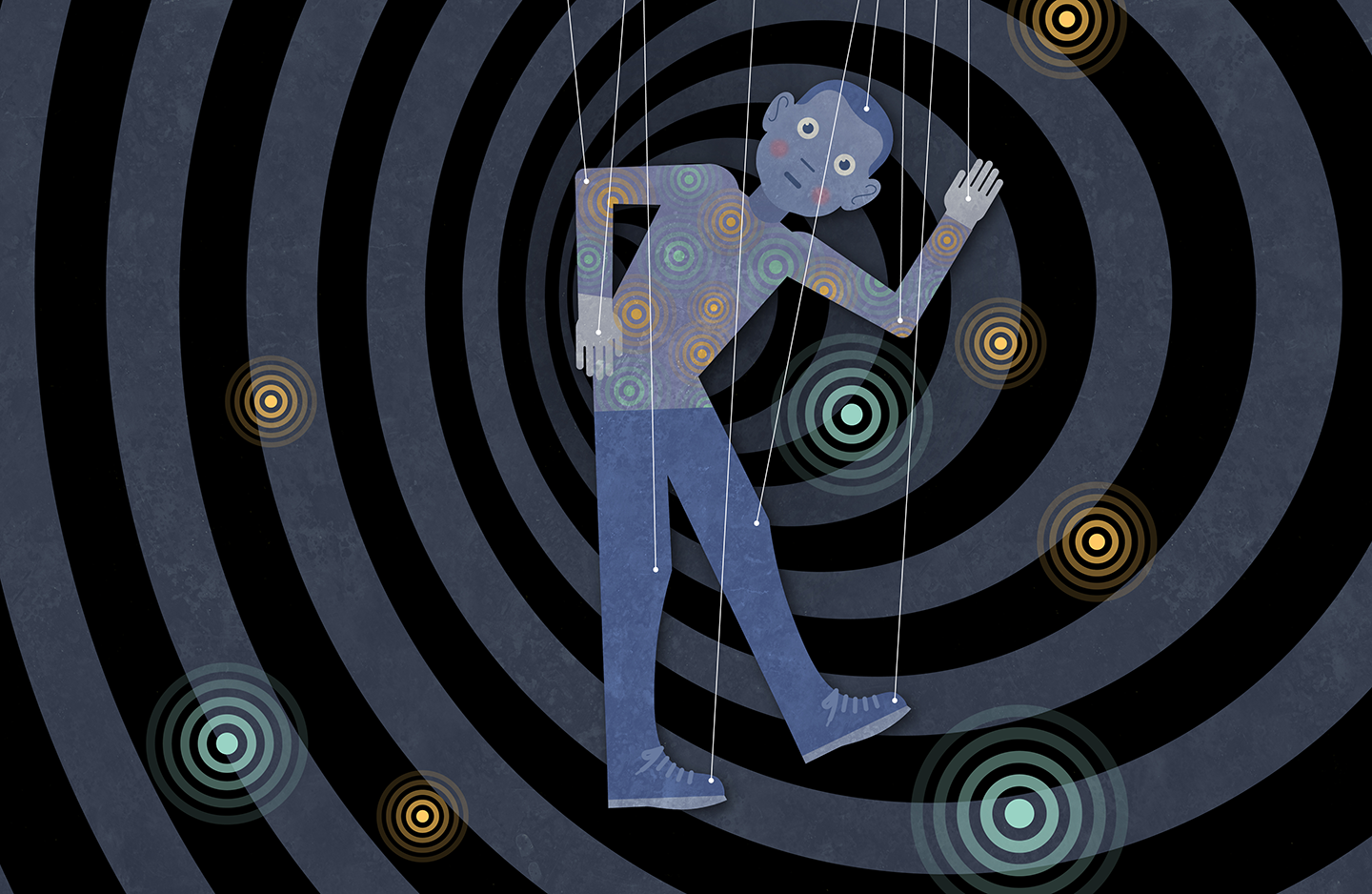

When Tina Hesman Saey was in middle school, she saw a hypnotist perform at a student assembly. At first, she was skeptical. She’d seen hypnosis on TV, and it seemed like a magic trick: flashy, but fake. After all, a hypnotist couldn’t really turn a bunch of strangers into mindless puppets … could they?

Sitting on the gym bleachers, Saey watched her classmates volunteer to be hypnotized. Prodded by the hypnotist, each kid did a silly task, like hop on one foot. But Saey wasn’t impressed. “They’re just pretending,” she thought. To prove it, she raised her hand.

The hypnotist had Saey sit in a chair and close her eyes. Then, he started speaking. Saey can’t remember what he said. But afterward, the hypnotist told her to put both hands behind her head and lace her fingers together. “Try to pull your hands apart,” she recalls him saying. “You won’t be able to do it, because your fingers are stuck.”

Saey scoffed. But when she tried to separate her hands, the strangest thing happened: Her fingers felt stuck!

“It made me feel really frustrated,” laughs Saey, now 57. Later, when the hypnotist told her to straighten another student’s bowtie, she again tried to ignore the suggestion. But again, she gave in to the urge to follow it.

“I was fully conscious and aware the whole time,” she says. Saey didn’t feel like she was being mind-controlled. “If he had told me to do something really bad, I think that I could have overcome that.” Yet when it came to the hypnotist’s harmless suggestions, Saey had a baffling impulse to just go with them.

“I didn’t really understand what hypnosis was, and I’m not sure I still do,” says Saey, now a reporter for Science News in Washington, D.C. “How does it exactly work? And why does it influence your behavior?”

Scientists often define hypnosis as a procedure that coaxes someone into a specific state of focused attention. In that mindset, some people report feeling as though suggested sensations are real. A suggestion might be as simple as a person’s fingers being stuck together. Or it might be as extreme as not feeling pain during surgery.

For decades, researchers have been grappling with the question of how hypnosis works. And they still have only rough ideas about the answer.

Studies of the brain and behaviors suggest that hypnosis is a real experience. Research has even offered some clues about who can be hypnotized, as well as what they can — and can’t — be compelled to do. But scientists are just starting to piece together how the brain achieves such feats of altered perception.

You’re not getting very sleepy

On stage or screen, hypnosis is often played as some sort of enchantment. A hypnotist murmurs magic words — perhaps while swinging a pocket watch — and voilà! Their victim falls into a sleepy trance during which they must obey any command.

There’s a lot wrong with that picture, however.

For one thing, hypnosis doesn’t require any special powers. A hypnotist is just someone “saying things to another person,” explains Amanda Barnier. They’re not using “magical words,” she adds. “They’re just words.” A cognitive scientist, Barnier works at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia.

The first step in hypnosis is called induction. A hypnotist might start by telling someone to close their eyes, relax and listen closely. “It’s really an invitation to focus less on the external world,” Barnier says. The idea is to focus more on the hypnotist’s words.

Once someone is in a deeply attentive state of mind, the hypnotist starts making specific suggestions. These are often phrased as statements: Your eyelids are too heavy to open. A fly is buzzing near your ear. Your hand has gone numb.

Some people report that such suggestions feel real — and outside their control.

People often are shocked by how they respond to such suggestions, Barnier says. Her team has hypnotized people to not recognize their own reflection or to feel like someone else is controlling their arm. “The cool thing is, all the ability is not the hypnotist,” Barnier says. “The genius of the thing is actually in the hypnotized person.”

In fact, people can hypnotize themselves by listening to recorded inductions. Their own brains are what shape their experiences.

That also means people can choose to not engage if they don’t want to. “They haven’t flipped into some state where they’re just being programmed,” Barnier says. In lab tests, hypnosis can’t force people to do anything. “If it sits uncomfortably with them,” she says, “they will open their eyes and say, ‘No.’”

Who’s hypnotizable

Not everyone who hears the suggestion that they see a stranger in the mirror will feel that’s true. Some people are simply more hypnotizable than others, it seems. Scientists measure how susceptible to hypnosis someone is by giving them suggestions of increasing difficulty.

Most people can experience easy suggestions, like their eyelids getting heavier. Very few experience difficult suggestions, such as seeing or hearing something that isn’t there. Or suddenly not being able to see or hear something that is there.

Why do people vary? “That’s one of the lingering big questions,” says Devin Terhune. He’s an experimental psychologist at King’s College London in England.

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores

“Some of the factors are … your beliefs and expectations,” Terhune says. The more someone expects hypnosis to work on them, the more likely it will. People who are more prone to absorption may be more hypnotizable, too. Absorption is when you get sucked into an imaginary world and tune out your surroundings.

Terhune’s research also hints that people who are less aware of their control over their own actions may be more hypnotizable. But any of these factors — or others — could play a role, he adds. “It seems rather to probably be a complex mixture of many different abilities.”

Reality check

Anyone who’s never been hypnotized may doubt that any of this is real. “It’s a kind of a psychological phenomenon that freaks some people out, because it’s like … ‘How do I know you’re just not lying to me?’” Barnier says.

Hypnosis researchers have had to come up with clever tricks to answer that question.

In one method, scientists invite two groups of people to work with a hypnotist they’ve never met. One group consists of highly hypnotizable people. They’re told to go through a hypnosis session as normal. The other group is full of people who aren’t hypnotizable. They’re told to fool the hypnotist into thinking they’re hypnotized.

The fakers act somewhat differently, Barnier says. “They can’t quite work out the nuances of what a genuinely hypnotizable person will do.”

In one experiment reported in 1959, for example, a hypnotist suggested someone hallucinate that a researcher was sitting next to them. Then, the hypnotist had the person turn around. The real researcher was sitting behind them.

When asked, the fakers claimed they could only see the researcher they’d been told to hallucinate. They assumed this is what a hypnotized person would say. But they were wrong. People who felt like they were truly in a hypnotic trance said they saw both researchers — the real and the hallucinated one.

Scientists have also taken brain scans of people during hypnosis. These studies have only examined small groups of people. But the scans hint that when someone says they’re experiencing a hypnotic suggestion, their brain activity matches that claim.

One study published in 2000 involved eight highly hypnotizable people. Under hypnosis, they were asked to perceive black-and-white images as being colorful and colorful images as being black-and-white. When those people were shown black-and-white images, those parts of the brain involved in color perception lit up. When they viewed colorful images, those parts of the brain quieted down.

Some scientists have used brain scans to try to tease hypnosis apart from everyday imagination. “Regions that become active when you imagine something are distinct from those that become active when you’re responding to a hypnotic suggestion,” Terhune says.

One 1998 study with eight highly hypnotizable people showed evidence for this. Researchers had people listen to real sounds, imagine sounds or receive a hypnotic suggestion that they were hearing sounds. While listening to real and suggested sounds, their brain activity showed similarities that didn’t appear during imagined sounds.

Inside the hypnotized mind

If hypnosis can make people truly see, hear or feel things that aren’t real, the natural next question is how.

“We’re not aware of a specific brain region or network that might be [causing] response to suggestion,” Terhune says. Basically, scientists can’t yet point to some “hypnosis center” in the brain. But they’re on the hunt for brain regions that might be involved.

One team recently ran a series of studies looking at the brains of people who were hypnotized or just normally awake. The team first took fMRI scans. These measure blood flow to track brain activity. EEG readings measured electrical chatter between brain cells. Yet another technique — called proton magnetic-resonance spectroscopy — probed brain chemistry.

Each experiment involved a few dozen people with lots of experience being hypnotized.

Scientists tracked brain activity after participants listened to a series of statements designed to lull them into hypnotic states. Their brains were also scanned after listening to a list of facts not designed to induce hypnosis. Researchers shared what they found in 2023 and 2024.

The fMRI scans taken during hypnosis revealed changes in brain connectivity across several regions. These included parts of the parietal, occipital and temporal areas. “Those regions are involved in a lot of different functions,” notes Mike Brügger. For instance, they play roles in our perception of ourselves and our awareness of our bodies. Brügger is a neuroscientist. He worked on this research at the University of Zurich in Switzerland.

The EEG readings showed more theta-wave activity during hypnosis. In the past, these waves have been seen during meditation. And the brain-chemistry data showed changes in the concentration of a molecule known as myo-inositol. This change happened when people reported being in an especially deep hypnotic state. It’s not clear, though, why this brain chemical in particular should be involved in hypnosis, Brügger adds.

Together, the findings offer a few more pieces to the hypnosis-brain puzzle. But much more research is needed to fill in the picture.

Helpful hypnosis

The science of how hypnosis works may not yet be settled. Still, people around the world use hypnosis all the time — and not just for entertainment. Some therapists offer to hypnotize patients so that they will feel less pain, sleep better, quit smoking or achieve other goals.

Scientists have run many clinical trials to investigate how much hypnosis can affect a range of health issues. Such studies have found “certain conditions for which hypnotherapy is very effective, some [where] it’s moderately effective and then some areas where it’s not effective at all,” says Gary Elkins. He’s a psychologist at Baylor University in Waco, Texas.

Hypnosis is well known to help some people manage pain, he notes. That includes short-term pain from injuries and medical procedures. It also includes long-term, or chronic, pain. “People have been able to undergo major surgical procedures under hypnosis,” Elkins says. “But those are highly hypnotizable persons.”

Dali Geagea is a hypnotherapist and researcher at the University of Sussex in England. One way to help someone through a painful procedure, she says, is to numb them through hypnosis. One suggestion might be: “Imagine there’s an anesthesia glove, and once you put it [on], all the sensations will leave your hand.”

One of her patients was able to have a tooth pulled with their mouth numbed this way. “But if at any point they say, ‘I feel pain,’ there is anesthesia available,” she adds.

Chronic pain requires other techniques. A hypnotist might suggest that on a daily basis, someone will feel less pain. They might also offer suggestions to manage flare-ups. “You tell them, ‘Every time you have pain, you just put your hands together,’” Geagea says. “‘Once you put your hands together, you feel that the pain is less.’”

In 2021, scientists reviewed 20 years of research on hypnosis to treat pain. These studies had examined pain from injuries, medical conditions and procedures. All compared people who received hypnosis to those who did not. Hypnosis did seem to lower someone’s pain. On average, it was about as useful as other mental techniques for soothing discomfort, such as mindfulness.

Hypnosis also seems promising for managing anxiety, Elkins says. A hypnotist might treat someone’s nerves by suggesting that they feel safe, confident and relaxed.

In 2019, researchers conducted a review of hypnosis research for relieving anxiety. Hypnosis seemed about as helpful as muscle-relaxation techniques and a type of talk therapy known as cognitive behavioral therapy. It was even more helpful when paired with one of these other types of therapy.

Hypnosis may ease other stress-related problems, too. Take irritable bowel syndrome. (It’s the term for a chronic condition that affects how the body processes solid wastes.) Whether hypnosis can lead to behavior changes — such as quitting smoking — is another question, Elkins says. “The research is mixed.”

Even for well-studied uses such as pain and anxiety, hypnosis is no magic cure. “Hypnosis isn’t good for everything for every person under every situation,” points out Barnier, at Macquarie. Yet how it’s been used in medicine shows strikingly the mind’s ability to shape our experiences of reality. And to Barnier, its benefits offer strong motivation to continue plumbing the depths of this mysterious state of mind.

“A lot of people think hypnosis is wacky,” Barnier admits. “Rather than being strange and weird, it’s actually a really valuable skill. But we don’t really know enough about [it].”