For more than 30 years, researchers have debated whether a fossil of a small but fierce dinosaur came from a teen Tyrannosaurus rex or some other species. Now two new reports come to the same conclusion: Despite its looks, this was no T. rex.

Two paleontologists debuted the first evidence for this on Oct. 30 in Nature. Lindsay Zanno works at North Carolina State University in Raleigh. Co-author James Napoli is at Stony Brook University in New York.

A little more than a month later, further support for their assessment emerged in the Dec. 4 Science. Using a different fossil, a second research team showed that what they had assumed to be a young T. rex was actually an adult Nanotyrannus.

Zanno and Napoli had been poring over an exquisitely preserved skeleton of a small tyrannosaur. It had been unearthed in Montana’s 67-million-year-old Hell Creek formation. And what they found can finally end the debate over this dino’s species, they say.

The skeleton was part of a famous fossil known as Dueling Dinosaurs. It features a small tyrannosaur entangled with possible prey — a horned, beak-mouthed, plant-eating dinosaur. Rock had entombed them together for millions of years.

The tyrannosaur now turns out to be a long-sought missing link for researchers. Many had hoped to show Nanotyrannus was a discrete species. And at long last, here was proof: the first known adult Nanotyrannus.

A number of its features set it quite apart from any T. rex.

Similar — but oh so different, too

The identity issue started, in a sense, back in 1942. That’s when researchers unearthed the skull of a small, sharp-toothed dinosaur. At first it appeared to be a Gorgosaurus. But in 1988, scientists reinterpreted that fossil. They dubbed this new “pygmy” Nanotyrannus lancensis.

Others challenged that description. Features in its 60-centimeter (2-foot) long skull strongly resembled T. rex. This skull appeared to come from a juvenile, they suggested. Since then, fossils of several other small tyrannosaurs turned up in the Hell Creek Formation. And each also was assumed to be a young T. rex.

The burden of proof was on Nanotyrannus to forge its own identity.

Zanno and Napoli now say they found it in the nearly complete fossil remains of a 6-meter (20-foot) tyrannosaur. That may seem big, but it would have been dwarfed by an adult T. rex. From snout to tail, one of those could span 14 meters (46 feet)!

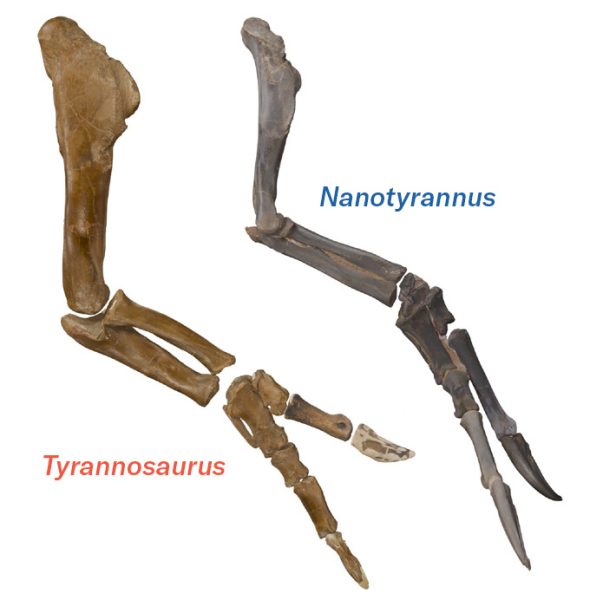

Growth rings in leg and arm bones of the small dino show that its skeleton was full-grown. This specimen also had the first preserved tail and arm bones of a Nanotyrannus. And both of these were unlike those in a T. rex. For instance, the tail of a T. rex has about 40 vertebrae. These had just 35.

But perhaps the most obvious difference, Zanno says, was its arms. “The arm of our Nanotyrannus is already [a bit] bigger than a T. rex arm.” And that’s despite its torso being a fraction the size of an adult T. rex’s.

Other telling differences include its respiratory system and traces of the brain’s nerves and sinuses on the skull. The pattern of these features don’t change as the creatures grow, Zanno explains.

Working with a different fossil, another team of paleontologists pored over the skull of what they had assumed was a juvenile T. rex. They focused on a group of throat bones. This hyoid has a simple, tubelike shape. And like limb bones, they tend to accumulate yearly growth rings, this analysis found. Those rings demonstrated the small skull had actually come from an adult N. lancensis.

“We converged on the same ultimate conclusion [as Zanno and Napoli],” concludes Christopher Griffin. Lead author of the second study, he works at Princeton University in New Jersey. What strengthens those conclusions, he says, is that the teams used “two very different lines of evidence.”

And a second species of Nanotyrannus?

With the aid of their newly identified adult N. lancensis, Zanno and Napoli reexamined Jane. It’s another long-debated dinosaur. Her bones showed she was a juvenile.

The two scientists compared her skeletal features to those of the Dueling Dinos fossil — as well as to more than 100 other previously analyzed tyrannosaurs. And Jane, too, was a young Nanotyrannus, not a young T. rex, they now conclude.

Jane, they suggest, was a new, slightly larger species than N. lancensis. They dubbed her species N. lethaeus after the River Lethe in Greek mythology. That river was said to bring forgetfulness to those who drink from it. And this dino’s name, Zanno says, alludes to the idea that Jane isn’t a new discovery: She’s been hiding in plain sight for decades.

The new analysis of the Dueling Dinosaur tyrannosaur bones “appears to show that the specimen is approaching adult size. And I am fine with that conclusion,” says Holly Ballard. She’s a paleontologist at Oklahoma State University in Tulsa.

But Ballard is not convinced that Jane is a new species of Nanotyrannus — or even a Nanotyrannus at all. Nearly six ago, she was the lead author of a paper first describing Jane’s skeleton. Even as a juvenile with more growth to come, she notes, Jane was bigger than N. lancensis.

Tyrannosaur neighbors

Nanotyrannus and Tyrannosaurus could have lived next to each other at the end of the dinosaur era. And they didn’t just coexist, Zanno says. They occupied different ecological niches in the same Hell Creek region.

“Nanotyrannus was a completely different kind of predator,” she says. “Small, slender, extremely fast, with large predatory arms.” And T. rex? It was bulky, heavily built, with a huge head and a powerful bite force. That adds to growing evidence that dinosaurs were still diverse and flourishing right up to the end. That came 66 million years ago, when an asteroid slammed into Earth.

“Every other tyrannosaur-bearing community had a couple of different tyrannosaurs in it,” says Thomas Holtz. The new report, he says, “actually makes Hell Creek less weird.” A paleontologist, Holtz works at the University of Maryland in College Park and did not take part in either new study.

A professed Nanotyrannus doubter, Holtz says the new study has “done a far better job advocating for [it] than anyone in the past. That’s all we wanted, those of us who were skeptics.”

The new discovery could have impacts far beyond identifying a new species or even highlighting the enduring diversity of tyrannosaurs. It throws a massive wrench into much of what we’ve come to understand about the life and times of T. rex, Zanno says.

It turns out, she says, that several decades of basic research on T. rex — how it moved, what it ate, how it grew and more — “all contain data that comes from two different types of dinosaurs.” In light of the new analysis, she says, such details now “need to be pulled apart and reexamined.”

Then there’s the other side of the coin, Holtz adds: “If Nanotyrannus is real — and it looks like it is — we now once again do not know what a teen T. rex looks like.”

But we might soon.

Holtz and Zanno both alluded to a fossil currently being prepared in Colorado at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science. It’s thought to be a true teen T. rex. If so, it’ll offer up yet another line of evidence on skeletal differences for researchers to wrangle over.