Throughout the living and tech world, lenses focus light to improve the resolution of images. In our eyes, these curved structures are made of cells. Plastic or glass lenses have served the same purpose in eyeglasses and cameras. Now an international research team has harnessed E. coli bacteria to work as super-tiny lenses.

Because these rod-shaped microbes are so tiny — about a tenth to hundredth the size of the smallest lenses now in use — they might find new uses, such as in environmental sensing.

Anne Meyer at the University of Rochester in New York led a group that unveiled the tiny microbe-based tech December 17 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Bacteria can focus light a bit. Meyer thought her team could improve this. With a computer, they showed that glass should help bacteria focus light even better.

The microbes don’t normally make glass. But some sea sponges do — they use it as a type of skeleton. “We were inspired,” Meyer says, “by the idea that these sea-sponge skeletons are really lightweight. And they have interesting optical properties.” As a synthetic biologist, Meyer tinkers with genes to make cells do new things.

A protein in the sponges grabs molecules from seawater to make their glass. That glass ends up looking like long needles. Each needle is similar to ones in the fiber optic cables used to carry internet signals. When you shine light on one side of the fiber or needle, light comes out very focused in one spot at the other end.

The researchers inserted a sponge gene into their E. coli. These genetically engineered microbes now are able to coat themselves with glass.

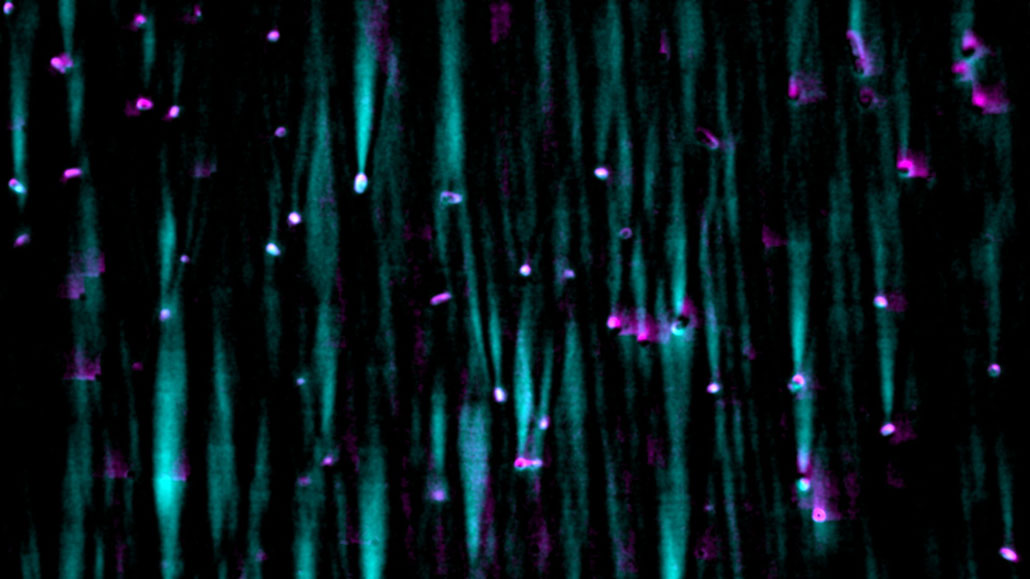

And when “we shine light at glass-coated bacterial cells, they could make a really bright jet of focused light on the other side,” Meyer reports. “That means they were acting like really, really tiny lenses.”

Living lenses

The glass-coated bacteria survived for months. Although they couldn’t move enough to divide, they remained active while tucked away in their shells.

“I was very impressed,” says Tom Ellis of the new lenses. He’s a synthetic biologist who did not take part in the new work. He works in England at Imperial College London. The new finding, he says, “shows us that it is possible for microbes to produce materials that then immediately form shaped structures with uses.”

“With bacteria-sized lenses, your cell-phone camera could be even thinner,” notes Meyer. “And the camera would be flexible,” she adds, so “you could bend it around a corner.” That’s because many tiny lenses together could move more easily than a few larger ones. These eco-friendly and low-cost lenses also could make photos clearer and crisper.

Living microlenses could have a range of other uses, too. “You might want to sense disease particles or the health of your cells,” says Meyer. And by having such small lenses, “these kinds of biosensors could be more sensitive,” she speculates.

An optical device made using such lenses might someday help monitor the environment. Living lenses might even be engineered to change color as critical conditions change — such as if a gas pipeline starts leaking. Then, people could quickly notice and fix it.

In new experiments, Meyer’s group is now changing the shapes of their bacteria. The first results show that super-long, thin bacteria can act as optical fibers — just like the sea-sponge needles.

The team also is looking into whether the lenses could be made in space. This might help people living on the moon or on Mars. They could make their own tools, like living lenses, instead of waiting for them to be shipped from Earth.

This is one in a series presenting news on technology and innovation, made possible with generous support from the Lemelson Foundation.

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores