Ammolites are some pretty fabulous fossils. Unlike many ancient life forms that get preserved in dull browns and grays, ammolites shimmer like rainbows. Their vivid hues make them prized gemstones often used in jewelry. But it’s been a mystery how the ammolites’ famous colors form — until now.

Ammolite comes from the fossilized shells of ammonites. These are extinct squidlike critters that swam the seas when dinosaurs walked the Earth. Scientists knew the secret to the fossils’ flair lay somewhere in their layers of nacre (NAY-ker). (This material is also known as mother-of-pearl.) But not all ammonite fossils boast brilliant colors. Neither do nautilus or abalone shells, which also contain nacre.

To find out what is behind ammolite’s flashy hues, scientists examined the crystal plates that make up its nacre. They also looked at the plates in other ammonite fossils. And they peered at these crystal plates in shells of the nautilus and abalone.

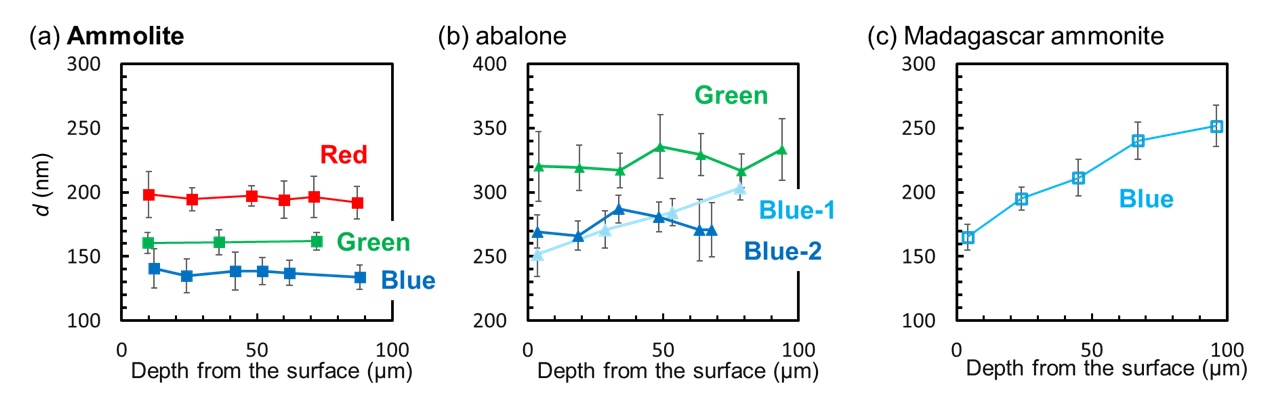

Two traits stood out in the ammolite’s plates. First, the thickness of its crystal layers tended to be uniform. Second, those plates were spaced out by gaps of just the right width. Only when the nacre had both did the ammolite’s iconic colors develop.

The researchers shared this discovery October 30 in Scientific Reports.

Under the microscope

Hiroaki Imai became enchanted by ammolite at a mineral fair in Tokyo. “I thought it might have some kind of special coating,” recalls this materials scientist. “I was astonished to learn it was the excavated fossil itself.” Imai works at Keio University in Yokohama, Japan.

He’s part of a team that looked at pieces of ammolite under electron microscopes. The gems came from the Bearpaw Formation in Alberta, Canada. Fossils there date back about 75 million years.

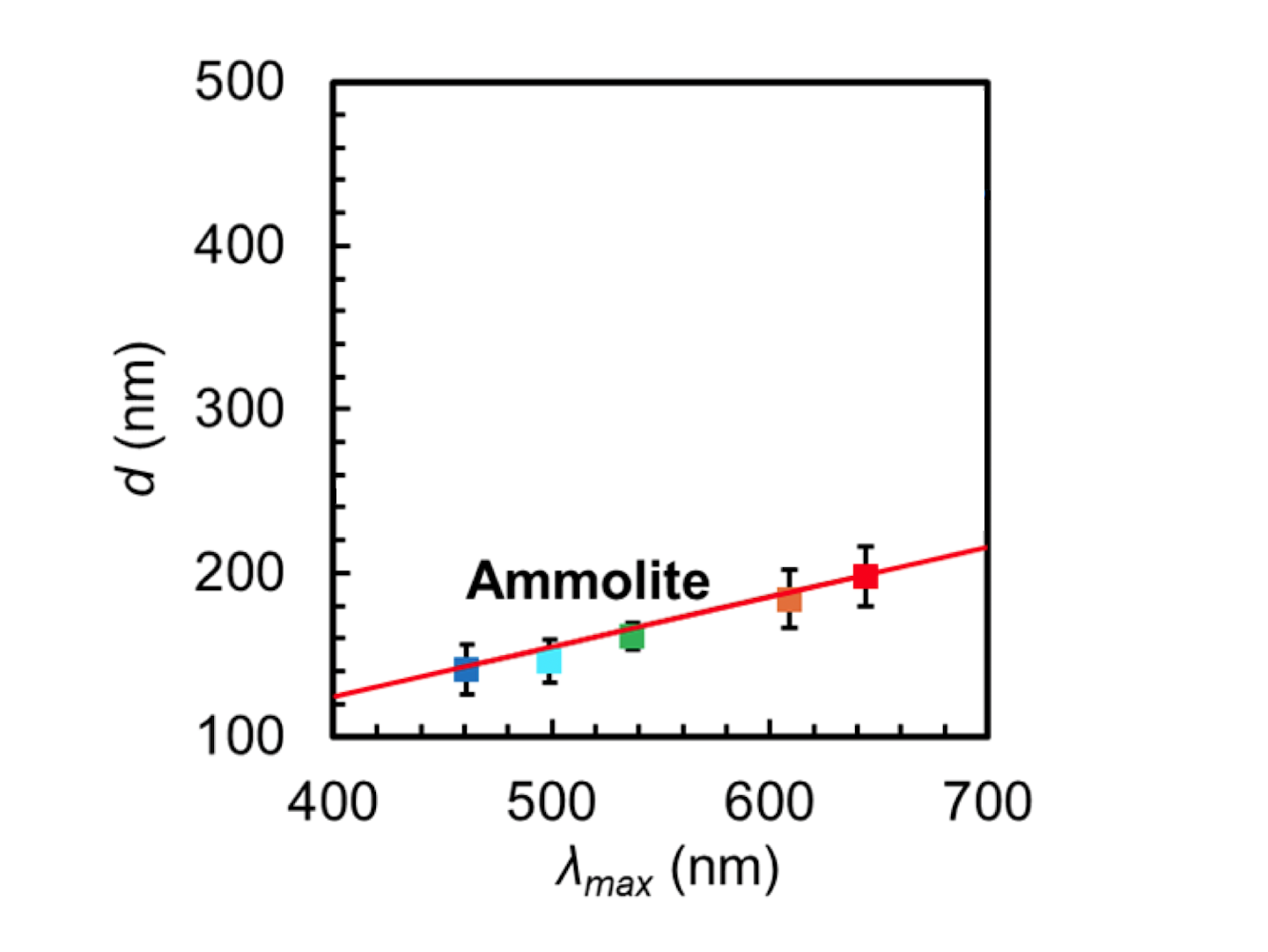

Ammolite pieces with thinner crystal plates reflected shorter wavelengths of light, his team found. That gave the gems deep blue hues. Pieces with thicker plates reflected longer wavelengths. These painted those pieces in rich reds.

The team could also see how ammolite’s structure differed from other, duller nacres. In ammolite, crystal plates were separated by thin pockets of air. Those pockets were about 4 nanometers wide — roughly twice the width of a DNA molecule. Organic (carbon-based) materials had worn away, leaving these gaps in the fossil. In abalone, 11-nanometer-thick layers of organic material still sat between its plates. And in a duller ammonite fossil from Madagascar, the plates had collapsed together, leaving no gaps.

Models revealed why 4-nanometer gaps were the sweet spot for bright, distinct colors. More tightly packed plates didn’t reflect as much light. That dulled their color. More widely spaced plates reflected many different wavelengths, muddling it.

Imai’s team also saw that the layers across a single piece of ammolite tended to have the same thickness. That helped the layers reflect distinct colors of light.

On to the next treasure

There may be a couple reasons why only some ammonite fossils produce ammolite nacre, Imai says. It might have to do with the species of ammonite being preserved. It also might depend on how the fossils had formed.

For its next project, his team is eyeing a different treasure: opals. These silica gemstones form through the weathering of rocks. “Some types of opal exhibit vivid structural colors,” Imai says. His team wants to see if a similar set of rules determine the colors in those gemstones.